“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so”

–attributed to Mark Twain

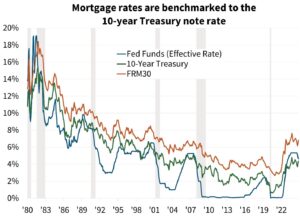

Many believe that the Federal Reserve sets mortgage interest rates. This is not true. Periodically it is good to remind everyone how mortgage interest rates are set. Here goes.

HOW ARE MORTGAGE RATES DETERMINED?

The interest rate controlled by the Federal Reserve is the federal funds rate which is the interest rate for overnight lending between banks. The federal funds rate is the interest rate used for very short-term lending. Interest rates on other short-term bonds and loans (like interest rates on credit cards) move very closely with changes in the federal funds rate.

The 15-year, 20-year and 30-year mortgage are long-duration loans, and thus have a different rate at which market participants are willing to lend versus a short-term loan, such as the federal funds rate. Mortgage rates are primarily benchmarked to the 10-year Treasury note. Therefore, movement in the 10-year Treasury has a significantly larger and more direct impact on mortgage rates than the federal funds rate.

Data sources for chart: Freddie Mac, Federal Reserve Board, Fannie Mae

Key Points

- The 30-year mortgage rate is benchmarked to the rate of the 10-year Treasury note. As the rate on the 10-year Treasury note moves, mortgage rates follow suit.

- The rate on the 10-year Treasury note is determined by investors’ expectations for shorter-term interest rates in the economy over the duration of the bond plus a term premium, which compensates investors for the risks associated with holding a longer-duration bond.

- Expectations of short-term rates are influenced by investors’ expectations for monetary and fiscal policy, economic growth, and inflation.

- Mortgage rates are determined by adding a spread to the benchmark 10-year Treasury note. The spread, or difference, between the rate offered on a 30-year mortgage and the 10-year Treasury note is determined by the Mortgage-Backed Security (MBS) market

What Determines the Rate on the 10-Year Treasury Note?

The rate on the 10-year Treasury note is determined by investors’ expectations for short-term interest rates over the 10-year duration of the bond.

Consider, as an example, an investor who is choosing between the 10-year Treasury note and a much shorter-duration 1-year Treasury bill. Instead of purchasing the 10-year Treasury note, the investor could purchase a 1-year Treasury bill and roll over their investment each year into a new 1-year Treasury bill for 10 years. The investor then would consider what they expect the rate on a 1-year Treasury bill (and other short-term rates) to be over the next 10 years to determine the interest rate they require to purchase a 10-year Treasury note. Because interest rates over a 10-year period are highly uncertain, investors take on additional risk when investing in a long-duration bond. Investors typically demand a higher interest rate, known as the term premium, on a longer-duration bond compared to a short-duration bond to compensate them for this additional risk.

Investors’ expectations for shorter-term interest rates, and thus the rate they are willing to accept on the 10-year Treasury note, are determined by their views on future monetary and fiscal policy, economic growth, and inflation.

- Monetary policy: The Federal Reserve sets the target federal funds rate to achieve its dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices. The federal funds rate provides a benchmark for other interest rates in the economy, particularly short-term rates. While current monetary policy has some impact on the 10-year Treasury note rate, investors’ expectations of future monetary policy are more important.

- Fiscal policy: Fiscal policy can affect economic growth and inflation. It can also affect the supply of government debt, depending on its impact on the federal budget deficit. When government debt issuance is high (or expectations are that it will be high), there is upward pressure on interest rates to attract sufficient demand to purchase government debt. Expectations for debt issuance may also affect the term premium.

- Economic growth: Economic growth affects monetary policy given the Fed’s dual mandate for price stability and maximum employment, as maximum employment generally relies on a strong economy. Additionally, economic growth affects the demand for bonds like the 10-year Treasury note. Investors who expect a stronger economy may seek other investment opportunities, such as equities. This causes demand for Treasury bonds to decline, pushing rates upward to attract investment. Conversely, if investors expect poor economic growth, they may seek a “safe haven” in Treasury bonds, causing rates to decline as demand rises.

- Inflation: Inflation impacts the stable prices side of the Fed’s mandate. Additionally, inflation causes a loss of purchasing power. If investors expect higher inflation, they will demand higher interest rates as compensation, while expectations for lower inflation cause investors to accept a lower interest rate.

The Mortgage Spread

The mortgage rate offered to borrowers is determined by adding a spread to the benchmark 10-year Treasury note. The mortgage spread can be broken into two major components:

- Primary-Secondary Mortgage Spread: Most mortgages are securitized into an MBS for investors to purchase. The spread between the mortgage rate that is offered to borrowers and the rate on an MBS is known as the primary-secondary spread. This spread reflects the costs of originating a mortgage and includes servicing fees, guaranty fees, and other lender costs and profits.

- Secondary Mortgage Spread: This represents the difference between the rate on an Mortgage Backed Security (MBS) and the rate on a 10-year Treasury note. Relative to the 10-year Treasury note, MBS’s carry two additional risks:

- Prepayment risk: Unlike the 10-year Treasury, which has a guaranteed rate for the duration of the bond, mortgage borrowers may prepay before the end of their mortgage term to refinance, move, or pay off their mortgage early.

- Credit risk: Whereas the 10-year Treasury is considered a virtually risk-free investment, a mortgage borrower or the entity providing a guarantee to the MBS investor may default.

To compensate for the additional risks of MBS, investors demand a higher interest rate on MBS compared to the 10-year Treasury note. From 1995 to 2005, the secondary spread averaged 1.17 percentage points and was particularly volatile. Following the Great Financial Crisis, from 2012 to 2019, the secondary spread averaged 0.71 percentage points and was more stable. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, from January 2022 through November 2024, the secondary spread has averaged 1.4 percentage points.

Following the Great Financial Crisis, the Federal Reserve began purchasing MBS and Treasury securities, a policy known as quantitative easing, to stabilize the financial system and drive interest rates, particularly mortgage rates, lower. The Fed is a non-economic buyer, which means it is not sensitive to the rate an MBS is paying. Therefore, when the Fed purchases MBS, it replaces private investors who are sensitive to the rate on MBS, which drives the secondary spread lower.

When the Fed does not purchase MBS to offset the ongoing runoff of MBS in its portfolio, a policy known as quantitative tightening, it gradually owns a smaller share of total MBS outstanding. As a result, private investors need to purchase that additional share, and as rate-sensitive buyers, they require a higher interest rate to do so. That’s why the secondary spread is driven upward when private investors replace the Fed in the MBS market.

A Look at Mortgage Rates Since 2020

When average mortgage rates hit a record low in December 2020, it was due to a 10-year Treasury rate that was well below its historical average at 0.93% and a compressed secondary spread of 0.45%. Both can be attributed, in part, to monetary policy, as the Fed kept the federal funds rate near zero and purchased significant amounts of both MBS and Treasury securities. Additionally, the outlook for economic growth was highly uncertain, and market participants considered U.S. Treasury securities to be a “safe haven” asset amid the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time, inflation was not a concern.

When mortgage rates hit their high of 7.8% in October 2023, the rate on the 10-year Treasury note had risen to a monthly average of 4.8%. Economic growth was strong, and inflation remained elevated well above the Fed’s 2-percent target. The federal funds rate was at 5.33% and the market expected a “higher for longer” policy stance from the Fed, meaning short-term rates were likely to stay high.

Additionally, the Fed’s balance sheet run-off put upward pressure on the secondary spread, which was elevated at 1.73 percentage points, as private investors sought higher rates on MBS to absorb the additional share. The rise in mortgage rates since the end of 2020 has been due primarily to an increase in the 10-year Treasury note rate and a widening in the secondary spread.

Following the September 2024 reduction in the federal funds rate, bond market investors have digested data releases that point to a stronger economy than many had expected, and somewhat-stickier inflation than previously thought. Given these developments, along with the results of the 2024 election, bond markets have priced in less monetary policy easing over the next two years. Previously, markets had expected the federal funds rate to be pushed below 3% by the end of 2026 (or even earlier), current market pricing now expects the Fed will keep rates closer to between 3.5% and 4%. Additionally, there is increased focus on the amount of Treasury issuance over the next few years. Combined, these developments have put upward pressure on the 10-year Treasury note rate, and thus mortgage rates.